You are here: Home >> Communications >> Member Publications >> White Papers >> HWE Evidence Review Series

Health Workforce Equity Evidence Review Series: Introduction & Summary

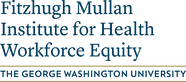

This series of evidence reviews aims to introduce readers to six domains of health workforce equity (HWE), understand how they are deeply intertwined, and consider some of the policy levers available to improve HWE. The six domains span: (1) who enters the workforce, (2) how they are educated and trained, (3) how they are distributed, (4) whom they serve, (5) how they practice, and (6) under what conditions they work.

Acknowledgement: This series was partially supported by the Kaiser Permanente Institute for Health Policy. We would like to thank Philip Alberti, Andrew Bazemore, Shannon Brownlee, Claire Gibbons, Erin Holve, Len Nichols, Luis Padilla, Murray Ross, and Michelle Washko for their review and feedback on both the framework and early drafts of the evidence reviews.

Domain 1: Who Enters the Health Workforce? An Examination of Racial and Ethnic Diversity

|

Black, Hispanic, and Native American individuals are underrepresented in health professions that require post-secondary education compared to their representation in the general population. A substantial body of literature suggests that a diverse and inclusive workforce can help increase access to care and improve health care outcomes among underserved populations. Conversely, the lack of diversity in the health workforce contributes to poorer health status for underrepresented populations and perpetuates historical health inequities. Numerous strategies can support the recruitment, matriculation, retention, and graduation of underrepresented minority students entering the health workforce. The literature suggests that the most effective strategies involve a multifaceted and comprehensive effort, spanning pipeline programs that offer academic support and mentorship to underrepresented minorities (URMs), URM-specific recruitment practices, holistic review in admissions processes, and federal programs and funding that support URMs. READ NOW

|

Domain 2: How is the Health Workforce Educated and Trained? An Examination of Social Mission in Health Professions Education

|

Institutions that provide health professionals with education and training play a critical role in determining whether clinicians graduate with the knowledge, skills, and courage to improve health equity. In the United States, there is still wide variation in their performance. The education pipeline plays an important role in determining the future workforce − who enters it, which professions are produced, and whether graduates choose high-need specialties, practice in underserved populations, and have the skills and courage to advance health equity. Among the policies and programs key to improving social mission goals are HRSA's Title VII and Title VIII workforce development programs, authorized under the Public Health Service Act, the Teaching Health Center Graduate Medical Education (THCGME) program, accreditation standards that influence educational institutions' policies and practices, certification and licensing exams which may or may not include topics such as health disparities, systems-based practice and social determinants of health in health professions exams or competency assessments; community-based, experiential clinical or service-learning experiences; and, lastly, the inclusion of social mission in governance documents and processes. READ NOW

|

Domain 3: Where and What Specialty Does the Health Workforce Practice? An Examination of the Geographic Distribution of Primary Care Providers

|

The primary care workforce tends to reside and practice in well-resourced communities. As a result, the primary care provider to population ratio is 93/100,000 in metropolitan areas, compared to 55/100,000 in non-metropolitan areas, leaving many rural and underserved communities with challenges in accessing care. There is strong evidence that this maldistribution contributes to health disparities. In addition, some policies and programs exacerbate the problem, including the current graduate medical education (GME) allocative system and unnecessarily restrictive scope of practice laws. While the methodology for designation of Health Professional Shortage Areas (HPSAs) is outdated and leads to a loss in allocative efficiency, many programs appear to help improve distribution, including recruitment of medical students from rural areas, partnerships between medical schools and community colleges, rural training tracks, career counseling and mentorship in rural and underserved areas, scholarships and loan repayment programs, and hub-and-spoke models of care in rural settings. READ NOW

|

Domain 4: Whom Does the Health Workforce Serve? An Examination of Provider Participation in Medicaid

|

Lack of access can be attributed to provider shortages and geographic maldistribution and the degree to which available clinicians provide service to communities made vulnerable. This evidence review focuses on provider service to low-income and publicly insured patients through Medicaid and the Children's Health Insurance Program (CHIP). Individuals with Medicaid are more likely to report access barriers than those with private insurance or Medicare, exacerbating inequities. 12 to 30% of primary care providers, depending on the state, do not serve Medicaid patients. Evidence suggests that state-level Medicaid policies, including lower payment rates relative to other payers and administrative burdens for reimbursement, represent barriers to provider participation in Medicaid. Other policies, such as the Primary Care Fee Bump, demonstrate mixed results. Policies that can increase provider participation in Medicaid include reimbursement fees and alternative payment models; expanded scope of practice and full reimbursement for advanced practice clinicians; increased funding for safety-net clinics; and Medicaid expansion under the Affordable Care Act. READ NOW

|

Domain 5: How Does the Health Workforce Practice? Addressing Root Causes of Health Disparities

|

There is mounting evidence that the current medical services model does not produce desired health outcomes, in large part because the health workforce has limited capacity to identify and address social determinants of health (SDoH). Evidence shows that this, in turn, can lead to improper care, poor health outcomes, and avoidable health disparities. While the health workforce cannot address the root causes alone, practicing to meet social needs, including eliminating racial disparities in care, helps ensure that everyone has a fair opportunity to attain their full health potential. Studies suggest that the fee-for-service payment model represents a significant barrier to addressing social determinants of health, while alternative payment models promise to address them. These models include value-based payment models such as accountable care organizations (ACOs) and the Comprehensive Primary Care Plus (CPC+). Other policies and programs that have some evidence supporting their use include SDoH screening, community health worker interventions, and interprofessional teams of clinicians and support staff. READ NOW

|

Domain 6: Under what Working Conditions? An Examination of Health Worker Compensation and Occupational Health

|

This review covers two parts: (1) Occupational Health, including injuries and illness, violence, and burnout, and (2) Worker Compensation.

Part 1 notes that the 22 million health workers in the U.S. experience the highest rates of occupational injury, illness, and burnout of any sector. This harm is preventable and in and of itself constitutes a health equity problem. Exacerbating the health inequity within the sector, the adverse effects impact different health occupations, genders, races, and ethnicities differentially and affect patient populations served by those most at risk differentially. Many organizational policies are key to improving health and safety, including ensuring safe staffing levels, team-based models of care, and the inclusion of medical scribes. Federal and state policies are also critical to establishing certain guardrails, including protecting workers' rights to unionize, expanding the scope of practice, and establishing and enforcing occupational safety procedures. Part 2 focuses on the nearly 7 million healthcare support workers that are severely under-compensated in the U.S., with almost half being paid less than $15 an hour and many lacking basic benefits like sick leave and health insurance. Poor compensation disproportionately affects women, people of color, and immigrants, exacerbating these communities' financial and social disadvantages. In addition, studies show that low compensation is associated with a high turnover of these workers, which negatively affects patients' health, particularly for Medicaid beneficiaries in long-term care facilities. Key federal policies to address this problem include increasing the minimum wage, protecting workers' right to unionize, and requiring sick leave and health care benefits. Increased Medicaid reimbursement rates could also help improve compensation if there are wage pass-through mandates. Value-based payment models may also facilitate wage increases for lesser-paid support staff. READ NOW |